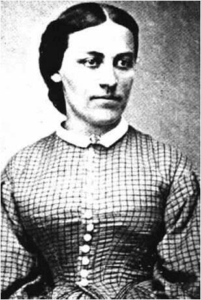

In late June 1863, Sallie Myers was a school teacher who had just turned 21. She was on summer vacation when Confederate forces invaded her hometown of Gettysburg and changed her life forever. She wrote in her diary that “on June 26 they came, spent the night and passed through… burning bridges and spreading consternation everywhere. Little we dreamed of the far greater horrors that were in store for us.”

Elizabeth Salome ‘Sallie’ Myers was born in Gettysburg on June 24, 1842. She was the daughter of Peter and Mary Myers and her father was a Justice of the Peace, and they were among the wealthier families in town. At the age of sixteen Sallie became a school teacher and in 1863 she was employed by the Gettysburg public school system as an assistant to the principal. She was living with her family on West High Street when fighting broke out west of town on the morning of July 1, 1863.

For three long days, the community of Gettysburg endured the raging battle. Houses, churches, and schools became makeshift hospitals. The town was left with thousands of dead and wounded soldiers, dead horses, and little food. Many homes and businesses were damaged or destroyed. Sallie described her experience as, “The noise above our heads, the rattling of musketry, the screeching of shells, and the unearthly yells, added to the cries of the children, were enough to shake the stoutest heart.”

Sallie wrote in her diary:

On Wednesday July 1, the storm broke. We were brimming over with patriotic enthusiasm. While our elders prepared food, we girls stood on the corner near our house and gave refreshments of all kinds to ‘our boys’ of the First Corps, who were double-quicking down Washington Street to join the troops already engaged in battle west of the town. After the men had all passed, we sat on our doorsteps or stood around in groups, frightened nearly out of our wits but never dreaming of defeat.

At 10 o’clock that morning I saw the first blood. A horse was led past our house covered with blood. The sight sickened me. Then three men came up the street. The middle one could barely walk. His head had been hastily bandaged and blood was visible. I grew faint with horror. I had never been able to stand the sight of blood, but I was destined to become used to it.

After being ordered to hide in her cellar she wrote:

We knelt, shivering, and prayed. The noise above our heads and from the distance, the rattle of musketry, the screeching of shells, and the unearthly cries, mingled with the sobbing of the children shook our hearts. Three soldiers crept down into the cellar, and we concealed and fed them.

After the Rebels had gained full possession of the town, some of our men who had been captured were standing near the cellar window. One of them asked if some of us would take their addresses and the addresses of friends and write to them of their capture. I took thirteen and wrote as they requested. I received answers from all but one, and several of the soldiers revisited the place of their capture and recognized the house and cellar window

There was a desperate need to care for the wounded and Sallie answered the call. She went to the nearby St. Francis Xavier Catholic Church, but the sights and sounds were too much and she ran outside to cry. All the rooms in Sallie’s home were kept full with the wounded, and she slept on the floor in the upstairs hall.

I went to the Catholic church. On pews and floors men lay, the groans of the suffering and dying were heartrending. From that time on we had no rest for weeks.

I knelt beside the first man near the door and asked what I could do. ‘Nothing,’ he replied, ‘I am going to die.’ I went outside the church and cried. I returned and spoke to the man – he was wounded in the lungs and spine, and there was not the slightest hope for him. The man was Sgt. Alexander Stewart of the 149th Pennsylvania Volunteers. I read a chapter of the Bible to him; it was the last chapter his father had read before he left home.

Sallie took Sgt. Stewart to her home to care for him. Unfortunately, Sgt. Stewart died on July 6 with Sallie by his side, tenderly caring for him. She notified his family and made sure that he was properly buried. Sallie received a letter from Alexander Stewart’s younger brother Henry, who was a minister. In the summer of 1864, Henry visited Sallie in Gettysburg and a romance kindled between them and they were married in 1867. Sadly, Henry died in 1868 from the effects of wounds he had suffered during the war.

Before long, Sallie returned to teaching and continued in this position until about 1905. She became involved with the National Association of Army Nurses, and served as its treasurer for twenty years, in recognition of her activity in nursing wounded soldiers during the Battle of Gettysburg.

In February 1869, Sallie gave birth a son whom she named Henry Alexander Stewart. Young Henry would grow up to become a physician and historian. In addition to helping establish the Adams County Historical Society, it was Henry who decided to type up his mother’s diary to preserve her memories of the battle.

Due to her courageous work in caring for the wounded at Gettysburg, Sallie was selected as a member of the National Association of Army Nurses. She was the only member in the history of the Association who was not a regularly enlisted Civil War Nurse.

Sallie Myers Stewart died of pneumonia on January 16, 1922 at age 79 and was buried in Evergreen Cemetery on Cemetery Hill in Gettysburg.

The sight of blood never again affected me, and I was among wounded and dying men day and night. While the battle lasted and the town was in possession of the Rebels, I went back and forth between my home and the hospitals without fear. The soldiers called me brave, but I am afraid the truth was that I did not know enough to be afraid and if I had known enough, I had no time to think of the risk I ran, for my heart and hands were full.

0 Comments