As Halloween approaches, tales of poisoned candy often seem like urban legends—but in 1858, a real-life candy horror unfolded in Bradford, Yorkshire, leaving over 200 people gravely ill and claiming the lives of 20 others. This tragedy, known as the Bradford Humbug Poisoning, reveals how a dangerous combination of high sugar prices, a common practice of candy adulteration, and a terrible mistake led to disaster.

So, how did arsenic-laced candy ever end up for sale?

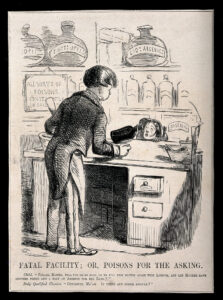

The root of the problem lay in the steep price of sugar. Because sugarcane couldn’t be grown in Britain, it was imported and heavily taxed, making it an exclusive luxury. In the 18th century, sugar was called “white gold,” fueling fortunes in trade hubs like Bristol. The sugar industry flourished with plantations in the West Indies, but even with 120 refineries by 1750, sugar remained costly. As a result, manufacturers cut production costs by “dafting”—a practice of blending sugar with cheaper, inert fillers like powdered limestone or plaster of Paris, harmless but decidedly unappetizing.

In October 1858, William Hardaker, or “Humbug Billy,” sold peppermint humbugs from a market stall in Bradford. The humbugs were peppermint lozenges, made by mixing peppermint oil into a base of sugar, water and gum, which was made into a paste, then dried on boards before being cut into lozenge shapes. Hardaker’s supplier, James Appleton, followed the usual dafting practice, purchasing filler from a local druggist. Tragically, this time, a critical mistake was made: 12 pounds of arsenic trioxide were sold to Appleton instead of the harmless ‘daft.’ Both substances looked similar as white powders, and the arsenic wasn’t properly labeled.

The public outcry following the Bradford Poisoning pushed for much-needed food safety reforms. Although charges of manslaughter were brought against those involved, no one was convicted. The incident led to the Adulteration of Food and Drink Bill in 1860, which aimed to regulate food production practices, and the UK Pharmacy Act of 1868, which enforced stricter controls on poisons in pharmacies.

In 1874, Britain finally abolished the sugar tax, making it affordable for everyone. But the horrifying Bradford incident remains a haunting reminder of the dangers hidden behind what should have been a simple, sweet treat. As you enjoy Halloween candy this year, remember—it wasn’t always so safe to indulge in sweets!

Classroom Connections

This story of the Bradford humbug poisoning offers a unique way to discuss broader historical themes, from public health and the impact of industrialization to economic history. Here are some engaging ways to incorporate this history into your classroom:

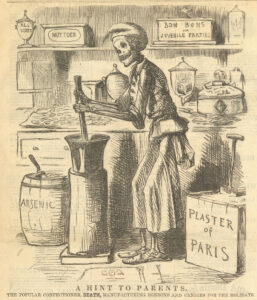

- Analyze “A Hint to Parents”

Use John Leech’s illustration, “A Hint to Parents,” to help students interpret historical satire. Have students examine how Leech portrayed the candy industry’s dangers through symbols and imagery. Challenge them to consider why Leech used the figure of Death as a candy maker. Discuss how this image would have impacted a public already fearful of food adulteration and how illustrations like this one could sway public opinion.

- Investigate the Economics of Sugar

Dive into the economic reasons behind food adulteration by examining the high cost of sugar in the 19th century. Ask students to research sugar’s origins in British trade and its role in the economy. You could set up a mock debate, with some students arguing as “confectioners” justifying the use of ‘daft’ to reduce costs and others representing consumers demanding safer food. - Science and Health Connections: What’s in Our Food?

Connect this history lesson with science by examining modern food safety regulations and how ingredients are tested for safety today. Encourage students to compare 19th-century practices with the modern USDA, FDA, or similar food regulatory agencies around the world. You could even do a fun, hands-on project where students read food labels and research any additives or preservatives they find. - Ethics in Public Health

Lead a discussion on ethics in public health, comparing the 1858 tragedy to more recent food safety incidents. Have students consider questions like: Should businesses be solely responsible for food safety, or should there be more government oversight? This exercise can encourage critical thinking about government responsibility and individual rights, a conversation relevant to many historical periods. - Primary Source Investigation

Share contemporary newspaper articles or pamphlets from the Bradford incident (many can be found in online archives) for a primary source analysis. Ask students to evaluate how these articles portray the event and public reaction. This activity could enhance their skills in identifying bias and recognizing how media shapes public perception, an essential skill for understanding historical context. - Debate on Accountability

Discuss the manslaughter charges brought against those involved in the poisoning, and then debate whether justice was served. Was this simply a tragic accident, or did it reveal negligence on the part of the confectioner, pharmacist, or government? This could tie into lessons on law and ethics, prompting students to think critically about responsibility in the face of public safety.

Use John Leech’s illustration, “A Hint to Parents,” to help students interpret historical satire. Have students examine how Leech portrayed the candy industry’s dangers through symbols and imagery. Challenge them to consider why Leech used the figure of Death as a candy maker. Discuss how this image would have impacted a public already fearful of food adulteration and how illustrations like this one could sway public opinion.

Use John Leech’s illustration, “A Hint to Parents,” to help students interpret historical satire. Have students examine how Leech portrayed the candy industry’s dangers through symbols and imagery. Challenge them to consider why Leech used the figure of Death as a candy maker. Discuss how this image would have impacted a public already fearful of food adulteration and how illustrations like this one could sway public opinion.

0 Comments